About the Archive

This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them. Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems. Please send reports of such problems to archive_feedback@nytimes.com.

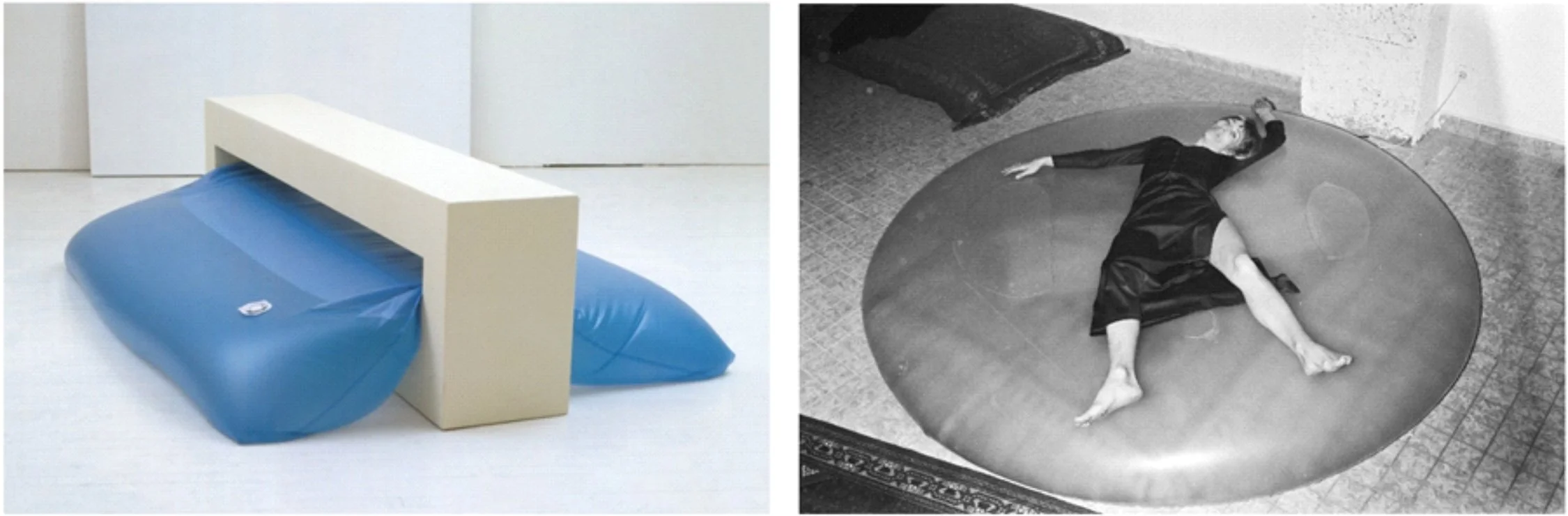

IT may never join the loftiest ranks of modern furniture design, those hallowed niches reserved for the likes of Mies van der Rohe or Charles Eames. And it is possible to overstate the cultural importance of the water bed. After all, the modern water bed began as a gurgling mass of velvet-topped vinyl, procured in bead-draped record stores along with incense and albums from the rock group Cream.

Still, if contributions to modern design were judged purely on the basis of emotions engendered, the water bed, that fluid fixture of 1970's crash pads, might be at the top of the ratings.

''A capitalist rip-off,'' a floor-loving purist said in Rolling Stone at that time. ''The bounciest bedroom invention since the innerspring mattress,'' said Time.

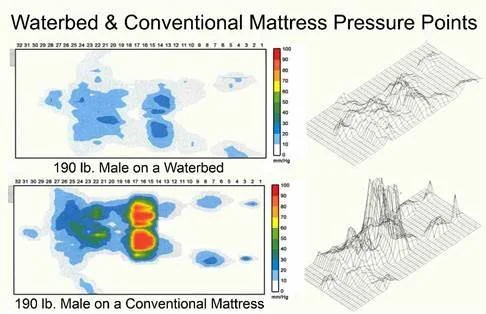

In the catalogue for last winter's ''High Styles'' show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Martin Filler called the water bed one of the ''most evocative furniture types of the time.'' Filled with up to 250 gallons of water and who knows how many tons of sexual promise, the organic, free-floating form seemed to capture the spirit of the age. Its mystique was skillfully perpetuated by water bed dealers and manufacturers. ''Two things are better on a water bed,'' read the copy of one popular advertisement in 1970. ''One of them is sleeping.''

But times change. ''When I was a hippie,'' says the San Francisco writer Ben Fong-Torres, a former water bed owner, ''I remember thinking that one day there would be a New Yorker cartoon in which you walked into an antique store and looked at beanbag chairs and water beds.''

Strangely, however, the water bed has not become passe. Rather, it has followed the path of granola and Jane Fonda. ''We have infiltrated the mainstream,'' says Henry R. Robinson, the president of the Trendwest Furniture Manufacturing Company and the official spokesman of the Waterbed Manufacturers Association.

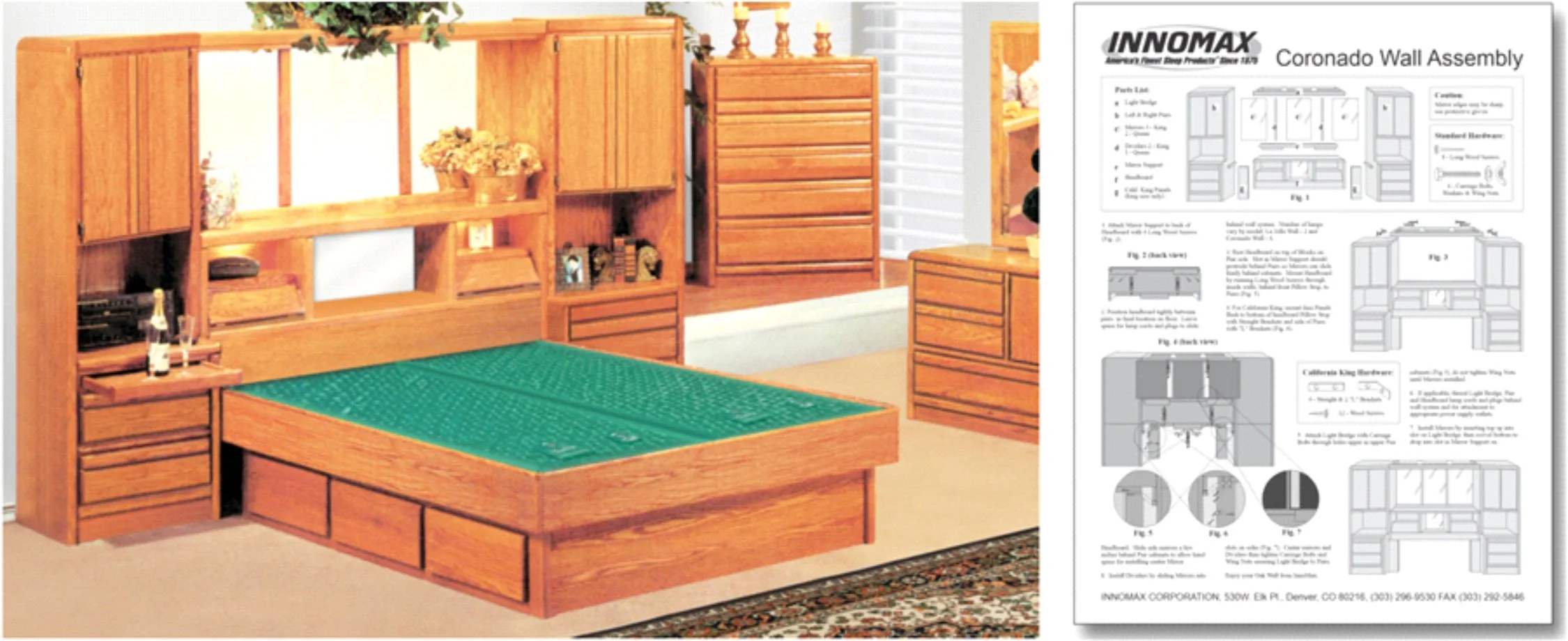

The $1.9 billion annual sales of the flotation sleep industry, as it is known, now constitute between 12 percent and 15 percent of the American bedding market, according to Mr. Robinson. In comparison, sales hovered around $13 million in 1971. Water beds now come in popular styles such as four-poster Colonials, which account for 49 percent of current frame sales. There are Victorian water beds with etched-glass and carved headboards. They are sold today in suburban shopping malls in stores with names like Waterbed Plaza. ''The water bed buyer profile is not distinctively different today from conventional mattress buyers,'' says Leonard S. Gaby, a vice president of Simmons U.S.A., which began selling water beds in 1980 and now offers five different styles.

In perhaps the biggest blow to their Haight-Ashbury image, water beds will be making their debut in the popular Spiegel catalogue next year, according to Carl Truett, furniture buyer for the company.

About the only place water beds do not seem to sell, in fact, is New York City, which has the distinction of being considered the nation's worst market for water beds. Manufacturers blame this on restrictions against them in apartment leases and the high costs of retailing, but David Klein, a vice president of Kleinsleep, a major New York bedding retailer, has another theory. ''New Yorkers are urbane, sophisticated,'' he says. ''By 1970, New Yorkers were bored with water beds.''

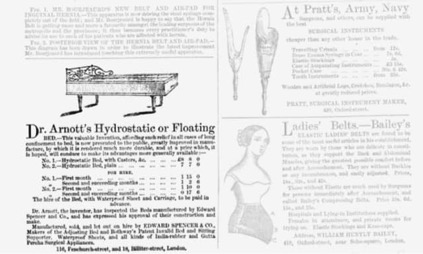

Born in 1969, the same year as Woodstock, the modern water bed was designed by Charles Hall, then a student, as a project for a class at San Francisco State University. Though therapeutic flotation systems date to the early 1800's, and possibly beyond, Mr. Hall is widely considered the inventor of the water bed in its popular form. The designer had originally turned to starch and Jell-O as a filler rather than water, but the goo tended to swallow the sleeper. This gave rise to newspaper feature headlines such as The Toronto Star's ''Rancid Jell-O Led to First Water Bed.''

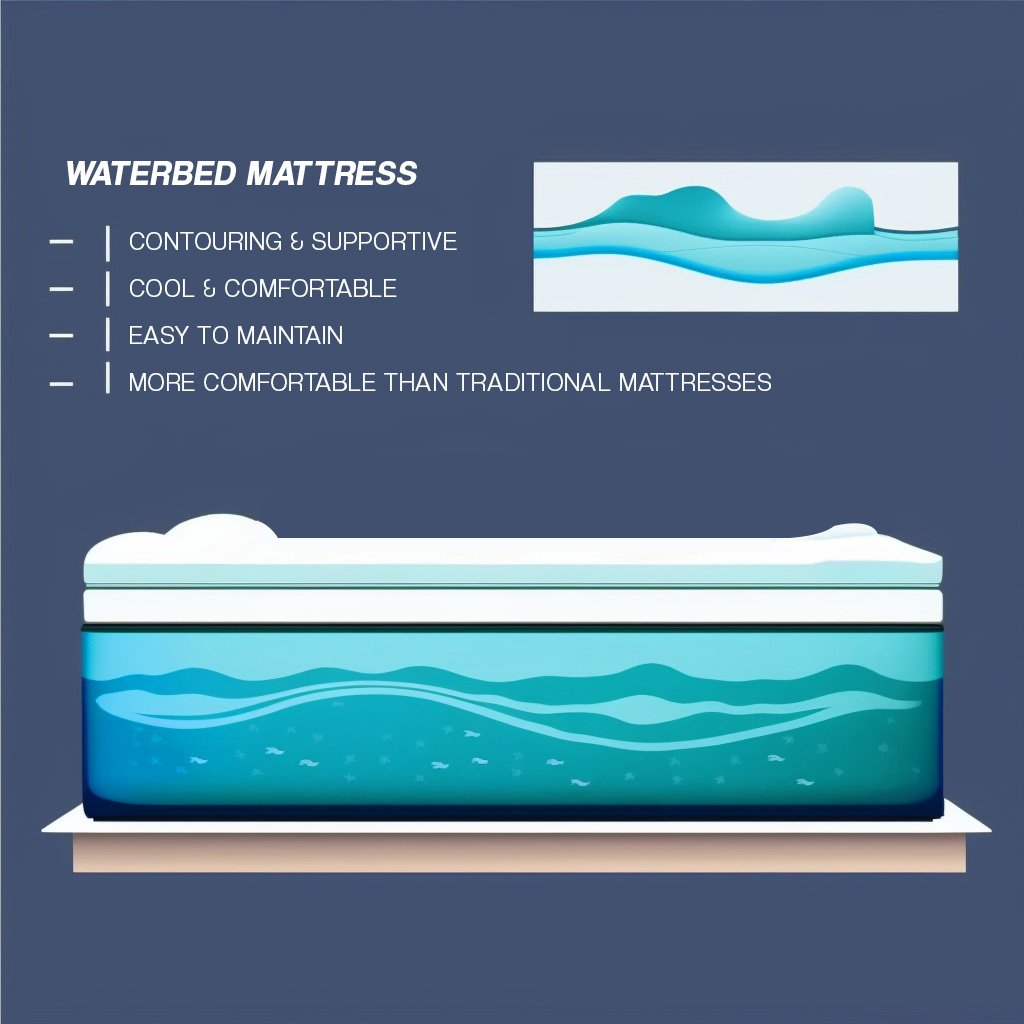

Eventually, Mr. Hall hit upon the right formula: a vinyl bag filled with water that was fitted with a temperature-control device and liner and set in a sturdy frame.

Mr. Hall's idea caught on instantly, but there were many cheap permutations. ''They were selling bags of water for $20,'' Mr. Hall says today. ''It was a disaster.''

Water beds became common on many college campuses, though their early reputation for leaks caused them to be banned by some campus housing authorities. A Vassar graduate of the early 70's, now a Manhattan banker, recalled, ''There was always a big scene in September with hoses hanging down from windows when someone moved their water bed in.'' She finally gave up on water beds, deeming them ''too squishy.'' David Klein said: ''It was a countercultural item. It was different. It was not the bed your parents had.''

In the mid-70's, stand-up comics and television sitcoms had a field day with water beds. In an episode of the sitcom ''Phyllis,'' for instance, Phyliss (Cloris Leachman) checked into a motel room only to discover a pink fur water bed. She later accidentally stabbed it with a letter opener, creating a geyser that gushed to the ceiling.

Such scenes created a profound image problem for the water bed industry. Mr. Robinson said: ''There was a stigma. The water bed was associated with sex, drugs and rock-and-roll, let's face it.'' Letitia Blitzer, 25 years old, of Bala Cynwyd, Pa., is emblematic of the water bed's image problem. ''They sort of looked left over from the 60's,'' she explains. ''I don't feel left over from the 60's. I can't tell you how fearful I was of having a garbage bag filled with water covered with psychedelic seagull and rainbow-decorated sheets.''

Nevertheless, at the instigation of her husband, Seth, also 25, the couple bought a water bed two years ago. Now, Mrs. Blitzer says, ''I'm glad I took the plunge.''

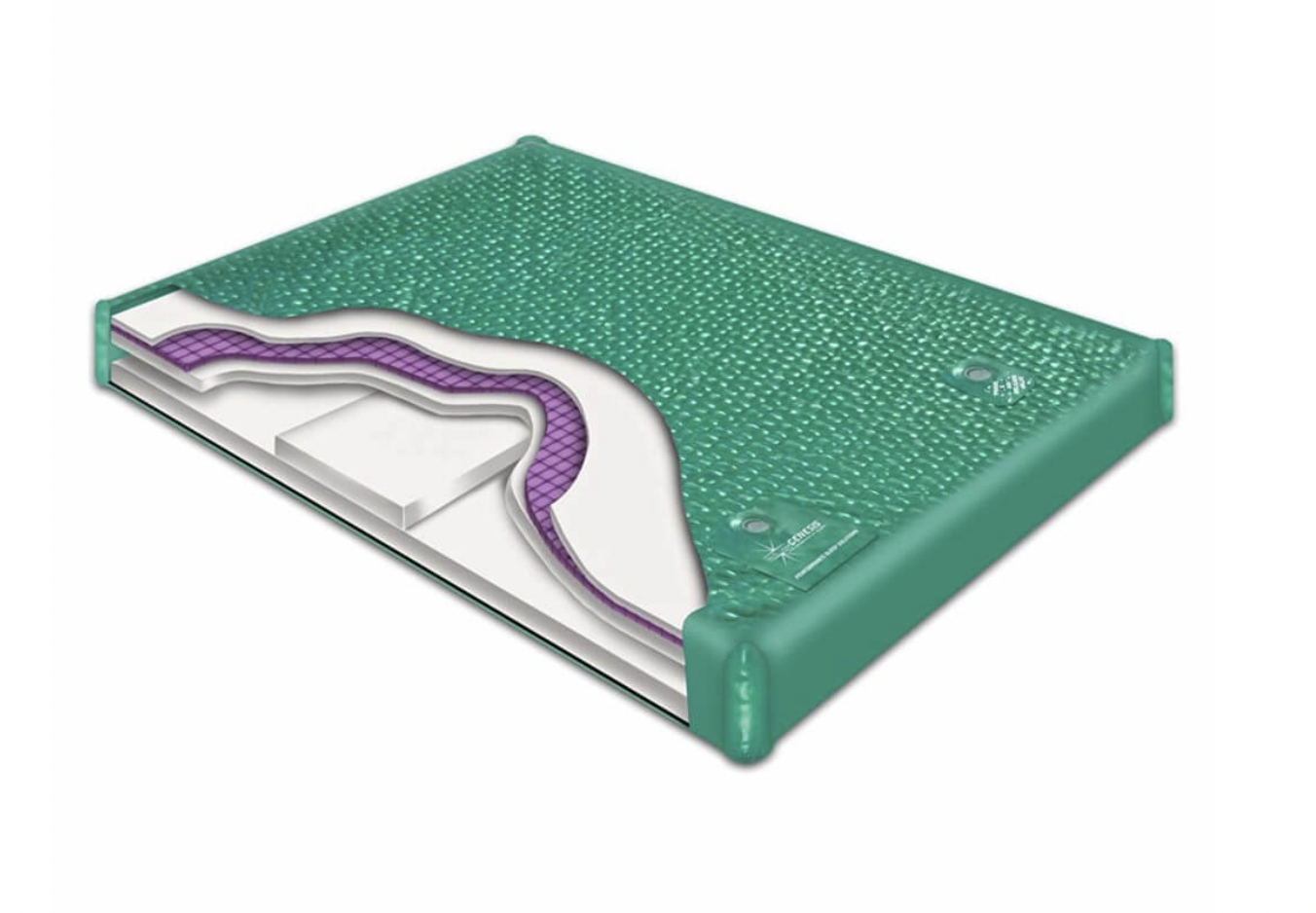

The advent of ''superwaveless'' mattresses has helped the water bed appeal to a more conventional market. The modification has ''made the water bed more of an adult product and taken away the major sales detriment,'' says Mr. Hall, who now designs beds for Monterey Manufacturing.

Perhaps the water bed, like so many other things in modern life, was bound to grow up. ''It's the old story of the counterculture becoming respectable,'' said Alan Dundes, professor of anthropology and folklore at the University of California at Berkeley.

''The country is in a different mood now than in the 1970's,'' he continued. ''There is a movement of conservatism. The family is coming back. There is a shift away from the self-indulgence of the 1970's.'' He hypothesized that the water bed ''had to undergo a metamorphosis and conform to an image of respectability in order to survive.''

Some of the water bed's original fans have changed, too. Marleen Nienhuis gave up the water bed she had purchased in Greenwich Village over 10 years ago, relegating it to her attic in New Jersey when she took a job on Wall Street. ''It unleashed a reservoir of emotions,'' she said of her decision, but somehow the idea of sleeping on a water bed and then going off to work at a major corporation didn't jibe.

In her place are new adherents, unfettered by history. ''I love it,'' said Annette Zullo, who has a four-poster waveless water bed with a carved headboard in her ranch house in Copiague, L.I. ''You can hardly tell it's a water bed.''

Still, despite its mainstream status, the water bed remains a powerful symbol of earlier, more spontaneous times. Observed Rod Lauer, owner of

Novembre Waterbeds in Baltimore, one of the nation's oldest dealers, ''People kind of smile when you say the word water bed.''